Managing Technical Migrations: The Enterprise Playbook

Introduction

Technical migrations are among the most challenging undertakings in enterprise technology. Whether migrating from on-premises to cloud, from a monolith to microservices, from one database technology to another, or from a legacy platform to a modern stack, migrations share common characteristics: they are expensive, risky, time-consuming, and essential. The cost of not migrating, perpetuating technical debt, missing market opportunities, and operating increasingly unsupported systems, eventually exceeds the cost of migration.

Yet the failure rate for large-scale technical migrations remains distressingly high. Studies consistently show that the majority of large migration projects exceed their budgets, miss their timelines, or fail to deliver the expected benefits. The failures are rarely purely technical. They stem from inadequate planning, poor stakeholder management, insufficient risk mitigation, and unrealistic expectations.

This playbook distills the strategic and operational principles that distinguish successful enterprise migrations from failed ones. It is not a technical guide to any specific migration type but a management framework applicable across migration contexts. The principles apply whether you are migrating a database, a data centre, a programming language, or an entire application platform.

Phase One: Strategic Planning and Assessment

The most consequential decisions in a migration are made before any technical work begins. The strategic planning phase establishes the migration’s business case, scope, approach, and constraints.

The business case must be specific and quantified. “We need to modernise” is not a business case. “Our current platform’s maintenance costs are increasing at twenty percent annually, it cannot support the product features our market requires, and the talent pool for its technology stack is shrinking by fifteen percent year-over-year” is a business case. The quantified business case provides the foundation for investment approval, progress measurement, and the inevitable moment when a stakeholder asks whether the migration is worth continuing.

Scope definition requires brutal honesty about what is and is not included. Migration scope tends to expand, both because the discovery process reveals unexpected dependencies and because stakeholders see the migration as an opportunity to address adjacent problems. Scope expansion is the primary cause of migration timeline and budget overruns. Define the scope explicitly, document what is excluded and why, and establish a change control process for scope adjustments.

The migration approach, whether big bang, incremental, or parallel-run, should be selected based on risk tolerance, business continuity requirements, and the nature of the systems being migrated. Big bang migrations, where the old system is replaced entirely on a cutover date, minimise the duration of operating two systems but concentrate risk in the cutover event. Incremental migrations, like the strangler fig pattern, distribute risk over time but require longer periods of dual-system operation. Parallel-run migrations operate both systems simultaneously and compare results, providing the highest confidence but the highest cost.

The assessment phase should produce a comprehensive inventory of the systems being migrated, their dependencies, data assets, integration points, and the teams and processes that depend on them. This inventory invariably reveals surprises: undocumented integrations, dependencies on deprecated features, and data quality issues that must be addressed before migration. Discovering these surprises during planning rather than during execution is one of the most valuable outcomes of thorough assessment.

Phase Two: Architecture and Execution Planning

With the strategic framework established, the architecture and execution planning phase designs the target state and the path to reach it.

Target architecture design should be driven by the business requirements that motivated the migration, not by the structure of the current system. A common trap is designing the target to be a modernised replica of the current system, preserving architectural patterns that were appropriate in the old context but are not in the new one. The migration is an opportunity to address architectural debt, not just technological debt.

The migration sequence, the order in which components are migrated, is a critical planning decision. Dependencies between components constrain sequencing. Business priority influences which capabilities are migrated first. Risk management suggests starting with lower-risk components to build team capability and confidence before tackling the most complex or critical components.

Data migration planning deserves disproportionate attention because data migration is typically the highest-risk and most complex aspect of any technology migration. Data must be mapped from source to target schemas, transformed to meet new system requirements, validated for completeness and accuracy, and migrated with minimal disruption to ongoing operations. The data migration strategy should be prototyped and tested early in the planning phase, not left as a later-phase activity.

Testing strategy must cover not just functional correctness but performance, security, integration, and regression. For migrations, validation testing, verifying that the migrated system produces the same results as the original for the same inputs, is particularly important. This requires comprehensive test datasets and comparison mechanisms.

Resource planning should account for the reality that migration work competes with feature development and operational maintenance. Dedicating a team solely to migration work, rather than asking teams to divide their attention between migration and feature delivery, consistently produces better outcomes. Migration work requires sustained focus and accumulates context that is lost when team members context-switch frequently.

Phase Three: Execution and Risk Management

Migration execution should follow the principle of progressive commitment: start with low-risk, high-learning activities and progressively commit to higher-risk activities as confidence and capability grow.

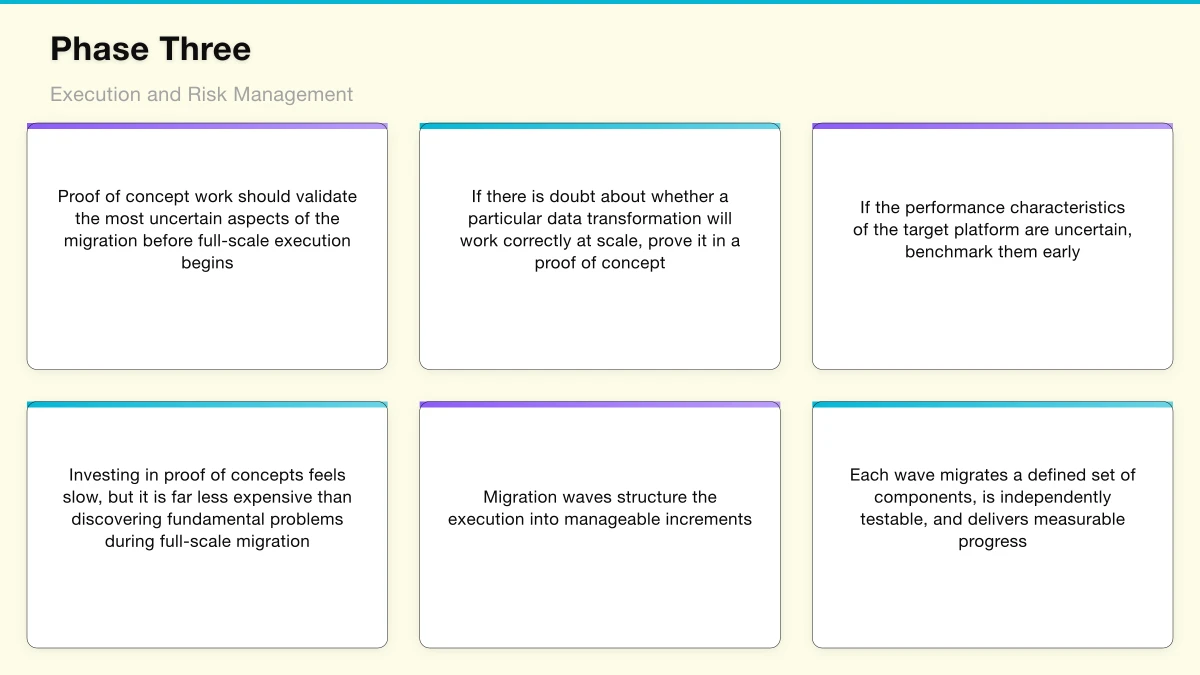

Proof of concept work should validate the most uncertain aspects of the migration before full-scale execution begins. If there is doubt about whether a particular data transformation will work correctly at scale, prove it in a proof of concept. If the performance characteristics of the target platform are uncertain, benchmark them early. Investing in proof of concepts feels slow, but it is far less expensive than discovering fundamental problems during full-scale migration.

Migration waves structure the execution into manageable increments. Each wave migrates a defined set of components, is independently testable, and delivers measurable progress. Waves should be sequenced to build on each other, with early waves establishing patterns and infrastructure that later waves leverage.

Rollback planning is essential for each migration wave. The ability to revert to the previous state if problems are discovered during or after migration provides the safety net that enables confident forward progress. Rollback procedures should be documented, tested, and time-bounded: if a problem is not resolved within a defined window, the rollback is executed rather than allowing an extended period of degraded service.

Risk management should be continuous throughout execution. A risk register, maintained and reviewed regularly, tracks identified risks, their probability and impact, mitigation actions, and owners. The most dangerous risks are those that emerge gradually: timeline drift accumulating week by week, quality issues that individually seem minor but collectively indicate systemic problems, and team fatigue that erodes the discipline needed for a successful migration.

Communication cadence should provide different stakeholder groups with appropriate information at appropriate frequencies. Executive stakeholders need monthly or bi-weekly progress summaries with clear status indicators and escalation of decisions that require their input. Technical stakeholders need weekly detailed updates on progress, blockers, and upcoming activities. Migration team members need daily coordination through standups or equivalent mechanisms.

Phase Four: Validation and Decommissioning

The final phase of a migration, validation and decommissioning, is frequently underinvested because organisational attention and energy shift to new priorities once the migration is perceived as substantially complete.

Validation should be comprehensive and systematic. Functional validation confirms that all migrated capabilities work correctly. Performance validation confirms that the target system meets performance requirements under realistic load. Integration validation confirms that all integration points function correctly. Business validation confirms that business processes produce correct outcomes in the migrated environment.

Decommissioning the legacy system should be planned and resourced from the outset. Legacy systems that remain running after migration consume operational resources, licensing costs, and management attention. Establish a clear decommissioning timeline and assign accountability for executing it.

Knowledge transfer and documentation should capture the lessons learned during migration, the architecture of the new system, and the operational procedures for managing it. Migration projects generate enormous institutional knowledge that is valuable for future migrations and for ongoing operation of the migrated system.

Post-migration review should assess whether the migration delivered the expected business benefits and capture lessons for future migrations. This review should occur after sufficient time has passed for the benefits to be measurable, typically three to six months after migration completion.

Technical migrations are marathons, not sprints. The enterprises that execute them successfully are those that invest in thorough planning, maintain disciplined execution, manage risks proactively, and sustain organisational commitment through completion. The playbook outlined here provides the framework; adapting it to each migration’s specific context is the art of enterprise technology leadership.