The CTO's Guide to Managing Legacy System Migration

Legacy systems are the backbone and the burden of enterprise technology. They process transactions, store institutional data, and support business processes that generate revenue. They also consume disproportionate maintenance budgets, resist change, and limit the organisation’s ability to innovate. The tension between these realities makes legacy migration one of the most consequential and most frequently botched initiatives in enterprise technology.

The statistics are sobering. Research consistently shows that large-scale legacy migration projects fail at rates exceeding fifty percent, measured by budget overruns, timeline extensions, or outright cancellation. The failures share common patterns: underestimated complexity, insufficient business engagement, aggressive timelines, and the mistaken belief that legacy migration is primarily a technology problem.

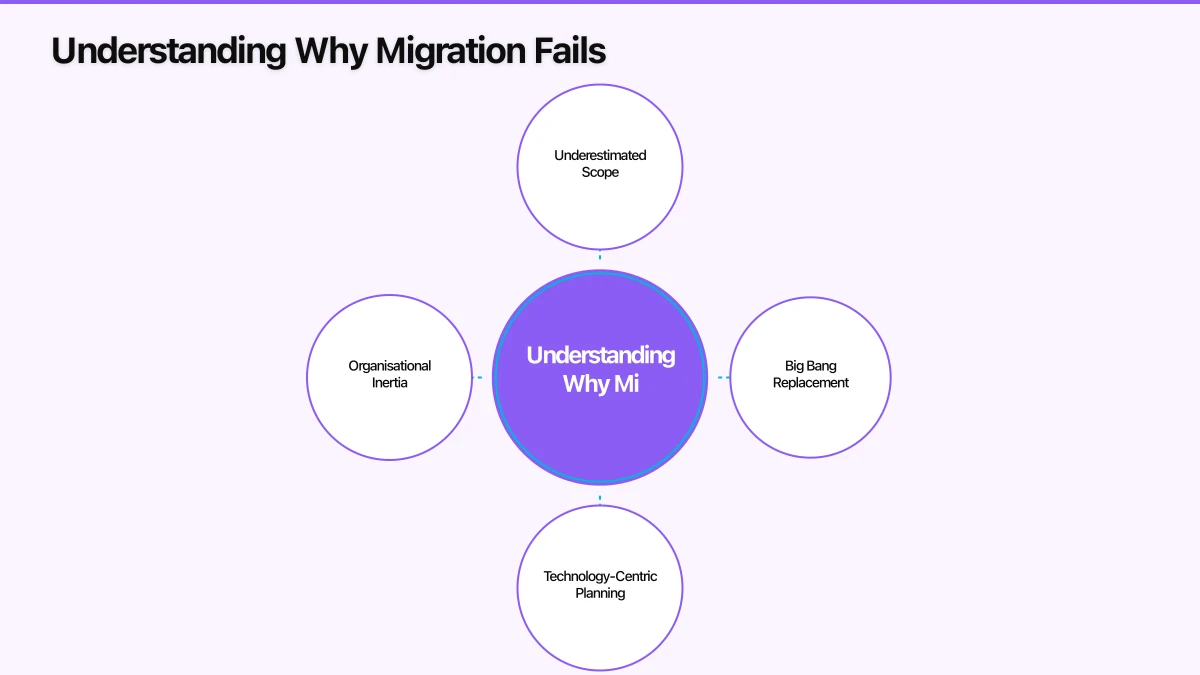

Understanding Why Migration Fails

Before discussing how to migrate successfully, it is worth understanding the failure modes in detail, because awareness of these patterns is the best defence against repeating them.

Underestimated Scope: Legacy systems are iceberg systems — the visible functionality represents a fraction of the total complexity. Business rules encoded in stored procedures, batch processing jobs that run on schedules no one remembers creating, integration interfaces consumed by downstream systems that were never documented, and edge cases handled by decades of incremental patches all lurk beneath the surface. Organisations that scope migration based on the visible system consistently discover that the actual system is two to three times larger.

Big Bang Replacement: The instinct to replace the legacy system entirely with a new system, cut over on a scheduled date, and decommission the old system is seductive in its simplicity and catastrophic in its execution. Big bang replacements concentrate risk: if anything goes wrong during cutover, the organisation faces a choice between operating a broken new system and reverting to the old system, which may no longer have current data.

Technology-Centric Planning: Migration projects led by technology teams without deep business engagement produce systems that replicate the legacy system’s technical architecture in a new technology stack without improving the business processes it supports. The organisation invests millions in rebuilding what it already had, with no new capability to show for it.

Organisational Inertia: The people who operate and maintain legacy systems have deep knowledge and established routines. Migration threatens both. Without deliberate change management, organisational resistance — manifested as risk amplification, requirements inflation, and passive non-cooperation — slows or derails migration initiatives.

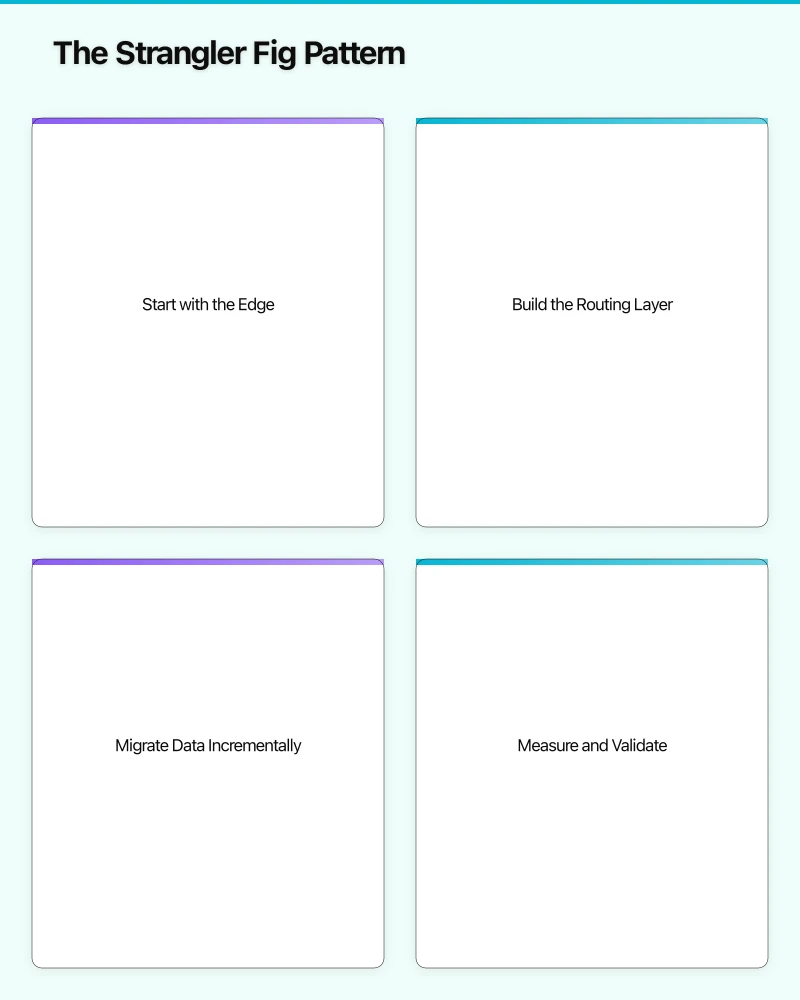

The Strangler Fig Pattern

Martin Fowler’s strangler fig pattern remains the most effective approach for legacy migration. Named after tropical fig trees that gradually envelope and replace their host, the pattern involves building new functionality alongside the existing system, routing traffic to the new system incrementally, and eventually decommissioning the legacy system when no traffic remains.

The strangler fig pattern succeeds because it manages risk through incremental change:

Start with the Edge: Begin migration with functionality that is relatively isolated, well-understood, and low-risk. New customer-facing features, reporting capabilities, or administrative functions often provide good starting points because they can be built on the new platform without modifying the legacy system’s core transaction processing.

Build the Routing Layer: A facade or routing layer sits between clients and both the legacy and new systems. Initially, all traffic routes to the legacy system. As new capabilities are built, the routing layer directs appropriate traffic to the new system. This layer is the key enabler of incremental migration — it allows old and new systems to coexist indefinitely.

Migrate Data Incrementally: Data migration is typically the hardest aspect of legacy migration. The strangler fig approach enables incremental data migration: the new system initially reads from the legacy database, then gradually takes ownership of data domains as capabilities migrate. During the transition, synchronisation mechanisms keep data consistent between old and new systems.

Measure and Validate: Each incremental migration step is a deployment that can be monitored, validated, and if necessary, reversed. Problems affect a small portion of functionality rather than the entire system. This incremental validation builds confidence and provides evidence of progress to stakeholders.

Data Migration: The Hidden Complexity

Data migration deserves special attention because it is consistently the aspect of legacy migration that causes the most problems.

Data Quality: Legacy systems accumulate data quality issues over decades — duplicate records, inconsistent formats, orphaned references, and data that violates constraints that were added after the data was created. Migrating this data to a new system with stricter validation produces errors that block migration unless they are addressed in advance.

A data quality assessment and remediation effort should begin months before the first data migration. This is not glamorous work, but it is essential. Organisations that discover data quality issues during migration face an impossible choice between delaying the migration or migrating bad data into the new system.

Schema Evolution: Legacy database schemas rarely map cleanly to modern data models. Decades of incremental changes, workarounds, and repurposed fields create schemas that are internally inconsistent and poorly documented. The migration must transform data from the legacy schema to the new schema, which requires deep understanding of both.

Dual-Write Complexity: During the transition period when both legacy and new systems are active, data changes must be reflected in both systems. This dual-write requirement introduces consistency challenges: what happens when a write succeeds in one system but fails in the other? Event-driven synchronisation patterns using change data capture (CDC) provide more reliable consistency than application-level dual writes, but add infrastructure complexity.

Cutover Strategy: The final data migration — moving the remaining data from legacy to new system and switching over — requires careful planning. The cutover window should be as short as possible to minimise business disruption. This means rehearsing the cutover process multiple times, optimising data transfer speeds, and having a rollback plan.

Organisational Change Management

Legacy migration is as much an organisational change as a technology change. The people dimension requires explicit management:

Business Ownership: The migration should be owned by the business, not by technology. Business leaders define the priority of functionality to migrate, validate that the new system meets business requirements, and make go/no-go decisions at each milestone. Technology teams execute the migration; business teams direct it.

Knowledge Transfer: Legacy system knowledge resides in the people who have operated and maintained the system for years. These individuals are essential during migration, but their knowledge is often tacit — embodied in experience rather than documented in specifications. Structured knowledge extraction sessions, paired working between legacy and new-system teams, and comprehensive documentation of discovered business rules capture this knowledge before it is lost.

Skills Transition: The people who maintain the legacy system need a path to the new technology. Some will transition to the new platform with training and support. Some will maintain the legacy system during the transition period and then move to other roles. A clear people plan that addresses career paths, training needs, and transition timelines reduces anxiety and resistance.

Stakeholder Communication: Regular, honest communication about migration progress, challenges, and timeline adjustments maintains stakeholder confidence. Legacy migrations always encounter unexpected issues. Organisations that communicate proactively about setbacks maintain trust. Organisations that hide problems until they become crises lose stakeholder support.

Legacy system migration is a test of enterprise technology leadership. It requires technical sophistication, business acumen, organisational empathy, and sustained commitment over years. The CTO who approaches it with the seriousness and humility it demands — acknowledging the complexity, planning for the unexpected, and investing in people as much as technology — maximises the probability of success in one of the most challenging initiatives in enterprise technology.