The Strategic CTO: Managing Technical Organisations Through Growth

The CTO role transforms fundamentally as an organisation grows. The CTO of a 10-person startup — writing code, making architecture decisions, and personally deploying to production — bears little resemblance to the CTO of a 500-person engineering organisation whose responsibilities centre on strategy, organisational design, and stakeholder management. Yet it is often the same person, navigating a role that reinvents itself every time the organisation doubles in size.

This transformation is one of the most challenging leadership journeys in technology. Many technically brilliant CTOs struggle as their organisations grow, not because they lack intelligence or work ethic, but because the skills that made them successful at one scale are insufficient or counterproductive at the next. Understanding the leadership transitions that growth demands, and developing the capabilities each transition requires, is essential for CTOs who want to scale with their organisations rather than being scaled out of them.

The Stages of CTO Evolution

The CTO role evolves through broadly recognisable stages, each demanding different skills, priorities, and operating modes.

The Builder (10-30 engineers): The CTO is the primary technical authority, often the strongest engineer on the team. Architecture decisions, technology selections, and coding standards flow from the CTO’s direct involvement. The CTO reviews most code, participates in incident response, and maintains deep familiarity with the entire codebase. Leadership is through technical expertise and personal example.

The key challenge at this stage is delegation. The CTO who builds everything personally creates a bottleneck that limits the team’s capacity. The transition requires hiring strong engineers and trusting them with decisions, accepting that some decisions will be different from what the CTO would have chosen. This is psychologically difficult for technical leaders whose identity is tied to technical contribution, but it is essential for growth.

The Architect (30-80 engineers): The CTO shifts from building to designing. Architecture decisions become the primary technical contribution, with the CTO establishing patterns, principles, and technical vision that guide multiple teams. The CTO hires and manages engineering managers, establishing the management layer that scales the organisation beyond what a single leader can directly oversee.

The key challenge is letting go of implementation details. The CTO who reviews every pull request, attends every design meeting, and approves every technology choice becomes the constraint that prevents the organisation from moving at the speed the business demands. The architect CTO establishes decision-making frameworks, not individual decisions.

The Strategist (80-200 engineers): The CTO’s focus shifts to technology strategy, organisational design, and cross-functional leadership. Technical contribution becomes increasingly indirect — through strategy documents, architecture principles, and the leaders the CTO hires rather than through code or detailed design. The CTO spends significant time with business stakeholders, translating business strategy into technology strategy and communicating technology capabilities and constraints to business leaders.

The key challenge is staying technically relevant while operating at strategic altitude. The CTO who loses technical grounding loses credibility with the engineering organisation and the ability to make sound strategic judgments. The CTO who remains mired in technical detail loses effectiveness as a strategic leader. The balance requires deliberate effort — staying close enough to technology trends, architecture decisions, and engineering challenges to maintain informed judgment while delegating the detailed work.

The Executive (200+ engineers): The CTO operates as a business executive whose domain happens to be technology. Responsibilities include board communication, investor relations, M&A due diligence, budget management, vendor negotiations, and cross-functional leadership on company strategy. The engineering organisation is managed through a leadership team of VPs and directors, with the CTO setting direction, removing obstacles, and ensuring alignment.

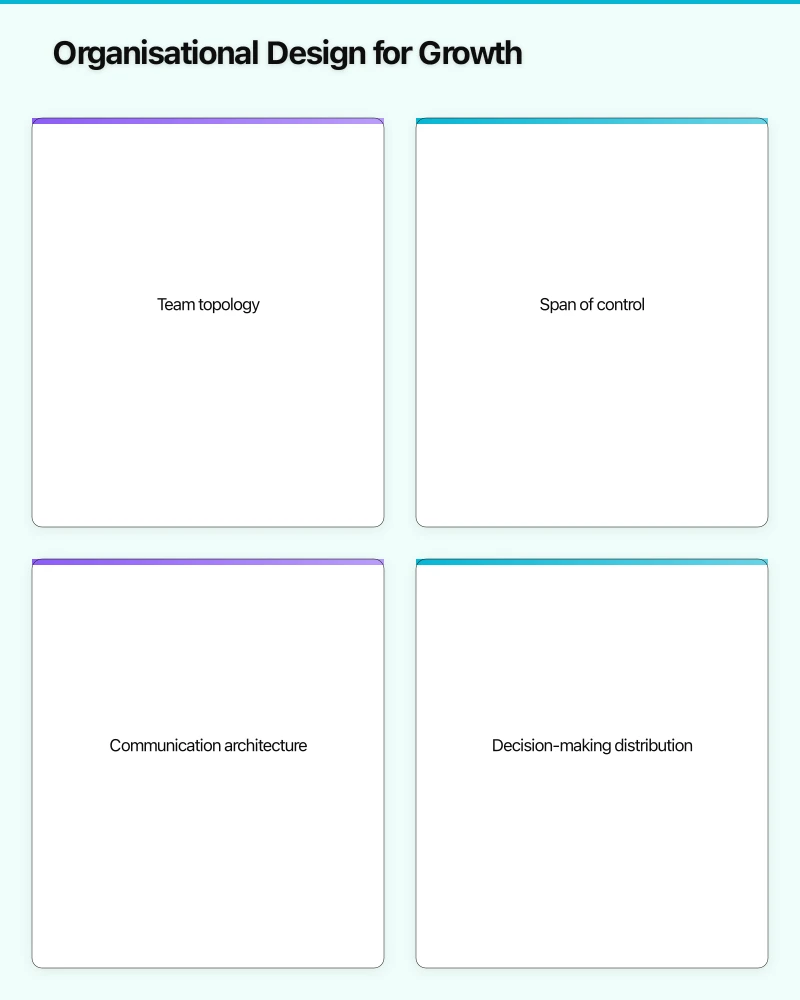

Organisational Design for Growth

As engineering organisations grow, their structure must evolve to maintain velocity, quality, and alignment. The organisational design decisions the CTO makes directly impact how fast the organisation can move and how effectively it can execute.

Team topology is the foundational organisational decision. The stream-aligned team model, where cross-functional teams are organised around customer-facing value streams, has emerged as the dominant pattern for modern engineering organisations. Each team owns a portion of the product experience end-to-end, including development, testing, deployment, and operations. This model minimises cross-team dependencies and enables autonomous delivery.

Supporting the stream-aligned teams are platform teams (providing shared infrastructure and tooling), enabling teams (helping stream teams adopt new technologies and practices), and complicated subsystem teams (managing components requiring deep specialist expertise). The balance between team types should favour stream-aligned teams, with supporting teams sized to serve the stream teams effectively.

Span of control determines management layer depth. The common guideline is 5-8 direct reports per manager, though this varies with experience level (senior engineers need less management) and work complexity (novel, ambiguous work benefits from tighter management). Too few reports per manager creates management overhead and unnecessary hierarchy. Too many creates insufficient support and career development for individual contributors.

Communication architecture mirrors organisational structure (Conway’s Law). The CTO should design communication patterns deliberately, recognising that the organisation’s software architecture will reflect its communication structure. Cross-team dependencies should be managed through well-defined interfaces (APIs, events, shared platforms) rather than ad hoc coordination.

Decision-making distribution is critical for organisational velocity. In growing organisations, the number of decisions increases faster than the CTO’s capacity to make them. Effective CTOs establish decision-making frameworks that distribute authority while maintaining alignment. The “reversible/irreversible” framework distinguishes between decisions that can be easily changed (deploy to most teams) and decisions with lasting consequences (retain at leadership level).

Hiring and Talent Strategy

The CTO’s hiring decisions have compounding effects — each hire influences the quality of subsequent hires and the capabilities of the organisation for years.

Hiring engineering managers is the highest-leverage hiring decision the CTO makes. Strong engineering managers multiply team performance; weak managers are the single most common cause of engineer attrition and team dysfunction. The CTO should invest disproportionate time in manager hiring, with rigorous assessment of technical judgment, people leadership, and communication skills.

Building a leadership team requires balancing complementary strengths. The CTO who is a brilliant strategist but weak at operational execution needs VPs who excel at execution. The CTO who is deeply technical but less commercially oriented needs leaders who bridge the technology-business gap. Self-awareness about personal strengths and gaps is the foundation of effective leadership team construction.

Culture as a hiring filter becomes increasingly important as the organisation grows. The engineering culture — how decisions are made, how quality is balanced with speed, how failure is treated, how disagreements are resolved — is established through the people the organisation hires. Every hire either reinforces or dilutes the target culture. Cultural alignment should be an explicit evaluation criterion, not left to intuition.

Diversity as a strategic advantage is both a moral imperative and a performance differentiator. Research consistently demonstrates that diverse teams make better decisions, produce more innovative solutions, and outperform homogeneous teams. CTOs should invest in diversity at every level — pipeline development, inclusive hiring practices, equitable promotion processes, and inclusive culture — as a strategic capability, not a compliance exercise.

Managing Through the Growth Challenges

Growth creates predictable challenges that CTOs can anticipate and prepare for.

Communication breakdown is the first casualty of growth. Information that flowed naturally in a small team requires deliberate processes in a larger organisation. The CTO must invest in communication infrastructure: all-hands meetings, written strategy documents, architecture decision records, and feedback mechanisms that keep the organisation aligned and informed.

Technical debt acceleration occurs when growth pressure prioritises feature delivery over codebase health. The CTO must establish sustainable practices — tech debt budgets, architecture review processes, quality metrics — that prevent the accumulation of debt that eventually slows the organisation to a crawl. Framing technical debt in business terms (reduced delivery speed, increased incident frequency, higher attrition) helps secure the investment needed for ongoing health.

Process resistance emerges when engineers who joined a small, informal organisation resist processes that growth necessitates. Code review requirements, architecture review boards, incident management processes, and planning ceremonies all feel like bureaucracy to engineers accustomed to direct action. The CTO must explain the why behind processes, ensure processes are genuinely lightweight and valuable, and adjust or eliminate processes that prove counterproductive.

Conclusion

The CTO’s journey through organisational growth is a continuous reinvention of role, skills, and impact. The technical mastery that launches a CTO career must be complemented by organisational design expertise, leadership capability, strategic thinking, and stakeholder management as the organisation scales.

For CTOs navigating growth in 2022, the essential discipline is self-awareness: understanding which stage your organisation is in, which capabilities the current stage demands, and which of your natural tendencies serve you well versus which need to evolve. The CTO who grows with the organisation — rather than constraining the organisation to the CTO’s comfort zone — creates lasting value. The CTO who resists evolution becomes the ceiling on the organisation’s potential.