Enterprise GraphQL: Federation Strategy for Large Organisations

GraphQL has demonstrated its value for API consumers — providing the flexibility to request exactly the data needed, reducing over-fetching and under-fetching that plague REST APIs, and enabling client teams to evolve their data requirements without backend coordination. For individual services, GraphQL is a proven technology. The challenge for enterprise adoption is scale: how does a large organisation with dozens or hundreds of microservices provide a unified GraphQL API without creating a monolithic gateway that becomes a bottleneck for every team?

Apollo Federation, introduced in 2019, provides the architectural answer. Federation enables multiple GraphQL services (called subgraphs) to be composed into a single, unified graph that consumers interact with through a gateway. Each subgraph is owned and operated by the team that owns the corresponding domain, preserving team autonomy while providing consumers with the seamless experience of a single API.

This is a significant architectural pattern for enterprises. It resolves the tension between the consumer desire for a unified API and the organisational need for distributed ownership. But federation introduces its own complexities — schema composition, performance management, error handling, and governance — that the CTO must address for enterprise-scale adoption.

Federation Architecture

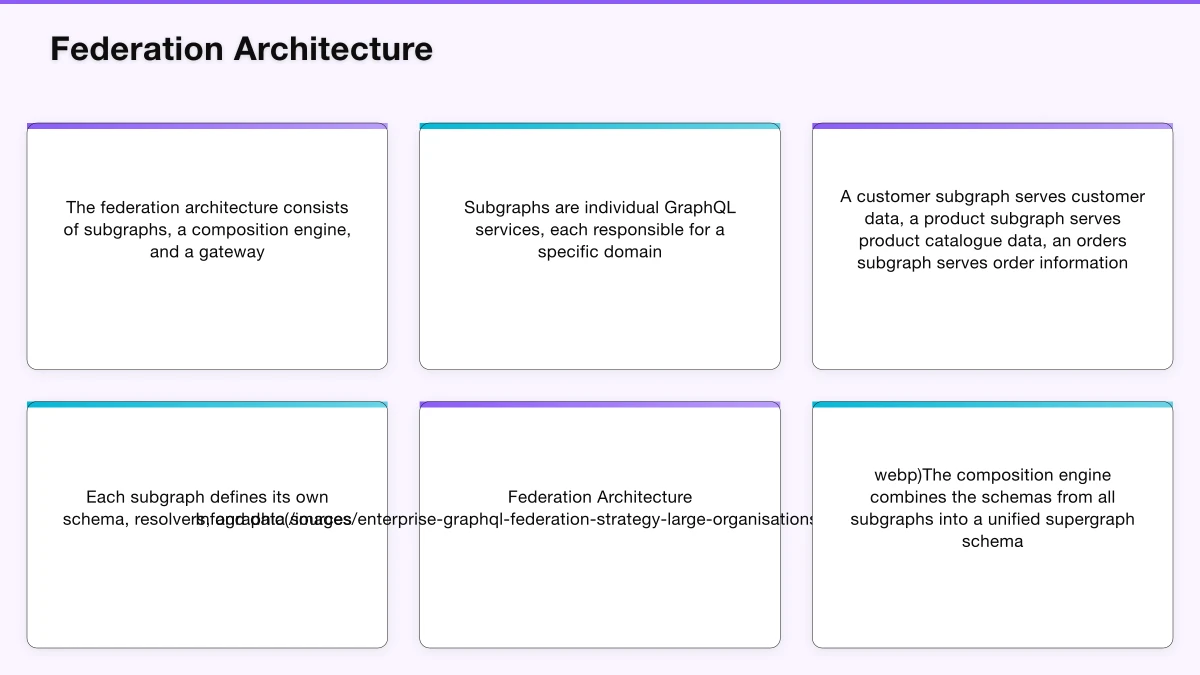

The federation architecture consists of subgraphs, a composition engine, and a gateway.

Subgraphs are individual GraphQL services, each responsible for a specific domain. A customer subgraph serves customer data, a product subgraph serves product catalogue data, an orders subgraph serves order information. Each subgraph defines its own schema, resolvers, and data sources. Critically, subgraphs can reference entities defined in other subgraphs — the orders subgraph can reference Customer entities defined in the customer subgraph, enabling cross-domain relationships without tight coupling.

The composition engine combines the schemas from all subgraphs into a unified supergraph schema. This composition validates that the schemas are compatible, that entity references resolve correctly, and that there are no conflicts between subgraph definitions. Apollo Studio (or the open-source rover CLI) provides composition capabilities, validating schema changes before they affect the production graph.

The gateway receives queries from consumers, plans the execution across the relevant subgraphs, fetches data from each subgraph, and assembles the response. Apollo Gateway (now Apollo Router, a high-performance Rust-based implementation) serves this function. The gateway is stateless and horizontally scalable, but it is in the critical path of every API request, making its performance and reliability paramount.

The execution planning that the gateway performs is sophisticated. A single consumer query might require data from multiple subgraphs, with dependencies between them — the order data must be fetched first to determine which customer IDs to look up, then customer data is fetched for those specific customers. The gateway’s query planner optimises this execution, parallelising independent fetches and minimising the number of subgraph requests.

Schema Design for Federation

Schema design in a federated environment requires conventions and governance that go beyond individual GraphQL service design.

Entity design is the most critical aspect. An entity is a type that can be resolved across multiple subgraphs. The Customer entity might be primarily defined in the customer subgraph (which owns name, email, and address) and extended in the orders subgraph (which adds an orders field). The entity’s primary keys, used to identify and resolve entities across subgraphs, must be carefully designed to be stable and performant.

The @key directive specifies how an entity can be identified. The @external directive marks fields that are defined in another subgraph. The @provides directive indicates which external fields a subgraph can resolve locally (from its own data store), avoiding additional subgraph calls. The @requires directive specifies fields from other subgraphs that must be fetched before a field can be resolved. These directives form the federation contract between subgraphs.

Schema ownership boundaries must be clear. Each field in the supergraph must have a single owning subgraph, and ownership should follow domain boundaries. The customer subgraph owns customer profile fields. The orders subgraph owns order-related fields. When the boundary is ambiguous — a customer’s order count could be owned by either subgraph — the decision should follow the domain that has the authoritative data source.

Schema evolution in a federated environment requires coordination. Adding a new field to a subgraph is generally safe — the composition will succeed and consumers can start using the new field. Removing or modifying a field is potentially breaking — consumers that depend on the field will receive errors. Schema checks, integrated into the subgraph’s CI/CD pipeline, validate proposed changes against the current supergraph and report any composition or compatibility issues before the change is deployed.

Performance Management

Federation introduces performance considerations that do not exist in monolithic GraphQL services.

The N+1 problem in federation occurs when the gateway must make separate requests to a subgraph for each entity in a list. If a query returns fifty orders, and each order references a customer entity resolved by the customer subgraph, the gateway could make fifty individual requests to the customer subgraph. Batching and DataLoader patterns at the subgraph level, combined with the gateway’s query planning optimisation, mitigate this issue, but it requires conscious design.

Query complexity limits prevent consumers from submitting queries that would be prohibitively expensive to execute. Depth limiting (restricting the nesting depth of queries), breadth limiting (restricting the number of fields at each level), and cost-based limiting (assigning costs to fields and limiting the total query cost) protect the graph from abusive or accidentally expensive queries.

Caching in a federated environment operates at multiple levels. The gateway can cache full query responses for queries that are executed frequently and have stable results. Subgraphs can cache entity resolutions to reduce data source load. Edge caching through CDN or API gateway caching can serve frequently accessed, infrequently changing data. The cache invalidation strategy must account for the distributed nature of the data — a change in the customer subgraph’s data should invalidate cached responses that include customer data.

Response time monitoring should track end-to-end latency, gateway processing time, and per-subgraph latency. This visibility enables identification of slow subgraphs that are impacting overall query performance. Distributed tracing, with trace context propagated from the gateway to each subgraph, provides detailed timing for each stage of query execution.

Governance and Organisational Model

Enterprise GraphQL federation requires a governance model that maintains graph quality while enabling team autonomy.

The graph steward role — an individual or small team responsible for the health and evolution of the supergraph — is essential. The graph steward defines schema standards (naming conventions, documentation requirements, pagination patterns), reviews significant schema changes, monitors graph health and performance, and facilitates resolution when subgraph boundaries or entity ownership is disputed.

Schema standards should cover naming conventions (consistent casing, pluralisation rules for lists, naming patterns for mutations), documentation requirements (every type and field should have a description), pagination patterns (cursor-based pagination using the Relay specification is the recommended approach for lists), and error handling conventions (consistent error types and codes across subgraphs).

The onboarding process for new subgraphs should be documented and efficient. When a team wants to add their domain to the federated graph, they should have clear guidance on schema design, entity definition, federation directive usage, and the CI/CD integration needed for schema validation and deployment.

Enterprise GraphQL federation is not merely a technology deployment — it is an organisational pattern that aligns API architecture with team structure. When executed well, it provides consumers with the unified, flexible API they desire while preserving the domain ownership and team autonomy that effective engineering organisations require. The CTO who invests in the governance and architectural foundations makes GraphQL federation a strategic asset for the enterprise.