Neuromorphic Computing: Building Chips That Think Like Brains

Introduction

In September 2024, Intel deployed its Loihi 2 neuromorphic research chip in partnership with Sandia National Laboratories to control a autonomous quadruped robot navigating complex terrain without GPS, relying instead on visual odometry and tactile feedback processed through spiking neural networks. The Loihi 2 system consumed an average of 140 milliwatts while processing sensory data in real-time—roughly 100× more energy-efficient than conventional GPU-based implementations performing equivalent computations—while achieving 23 millisecond latency for perception-to-action cycles enabling the robot to respond to obstacles faster than traditional control systems. The neuromorphic chip contained 1 million artificial neurons organized in event-driven architecture where neurons fire only when receiving sufficiently strong inputs (mimicking biological neural activity), with reconfigurable synaptic connections enabling online learning that adapted the robot’s behavior to new terrain types within 15 minutes of deployment without requiring retraining on external compute infrastructure. This demonstration exemplifies neuromorphic computing’s promise: by emulating biological neural networks’ event-driven, massively parallel, low-power operation, neuromorphic chips can enable intelligent edge devices—from autonomous vehicles to medical implants to IoT sensors—that process information efficiently in real-time without cloud connectivity or battery-draining conventional processors. As AI deployments expand from data centers to billions of resource-constrained edge devices, neuromorphic computing is emerging as critical technology for enabling intelligence everywhere.

The Brain-Computer Gap: Why Conventional Computing Is Inefficient for AI

Modern artificial intelligence achieves remarkable capabilities through deep neural networks trained on GPU clusters and deployed on power-hungry inference accelerators—but this approach differs fundamentally from biological intelligence in ways that create severe energy and latency inefficiencies. The human brain consumes approximately 20 watts (similar power to a dim lightbulb) while performing perception, reasoning, and motor control tasks that require megawatts of power when implemented on conventional digital hardware. Understanding this efficiency gap motivates neuromorphic computing’s design principles.

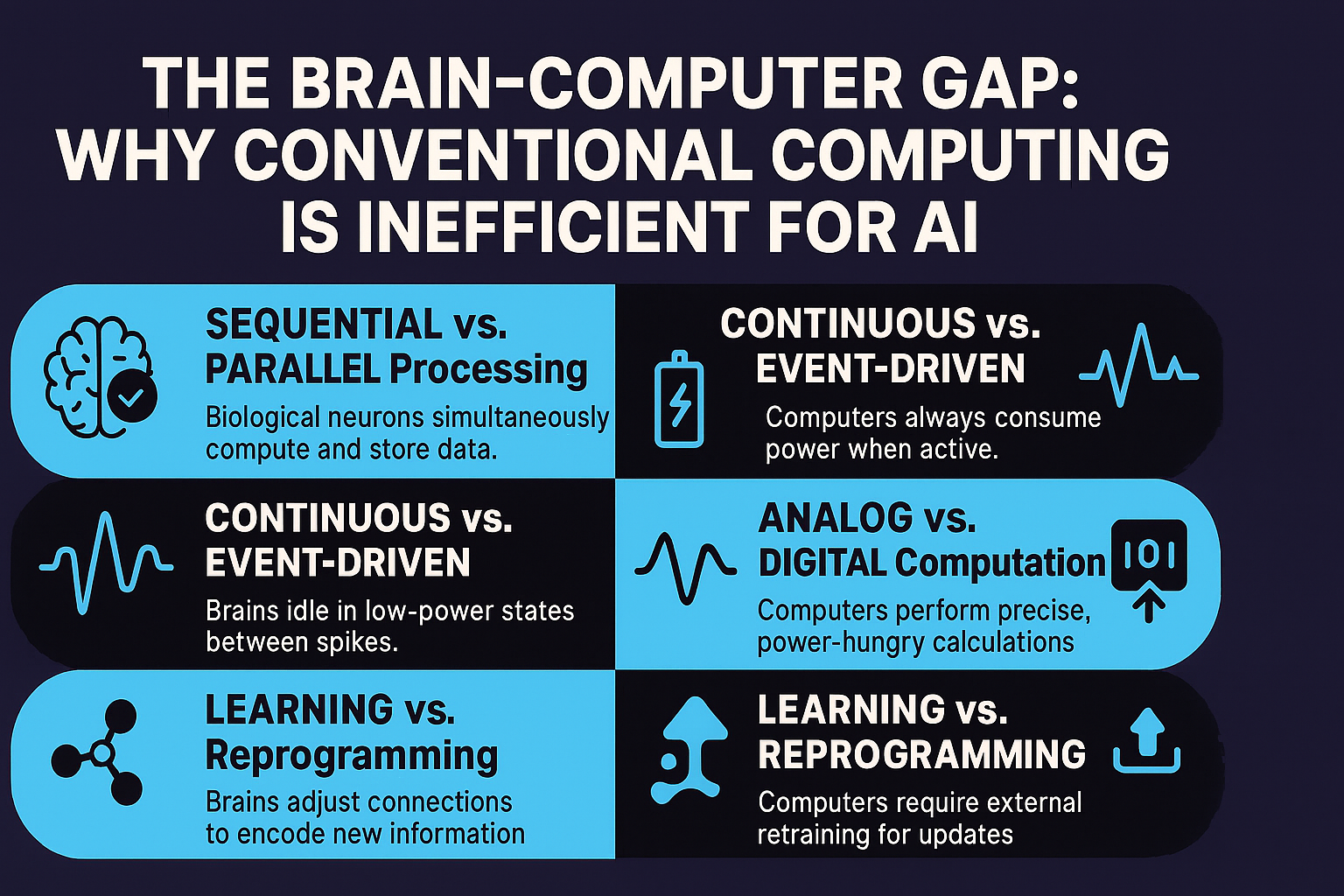

Sequential versus parallel processing represents the first fundamental difference. Conventional computers based on von Neumann architecture feature separate memory and processing units connected by limited-bandwidth buses, requiring data to shuttle between memory and ALUs (arithmetic logic units) for computation—a bottleneck that dominates execution time and energy consumption for data-intensive AI workloads. Graphics processing units (GPUs) mitigate this through massive parallelism (thousands of cores), but still follow the fetch-execute-store paradigm where computation and memory remain separate. In contrast, biological brains feature collocated memory and computation: synapses simultaneously store connection weights and perform multiply-accumulate operations as ions flow through channels, eliminating data movement overhead. Research from MIT analyzing energy consumption of deep neural network inference found that 90-95% of energy is spent moving data between memory hierarchies (DRAM ↔ cache ↔ registers) rather than performing actual computations—an inefficiency that biological systems avoid through in-memory processing.

Continuous versus event-driven operation creates the second efficiency gap. Conventional digital systems use clock signals to synchronize computation, with transistors switching at regular intervals (gigahertz frequencies) regardless of whether useful work occurs—wasting energy during idle periods. NVIDIA’s H100 GPU consumes 700 watts continuously even when utilization is low, because clock-driven logic maintains synchronization overhead. Biological neurons operate asynchronously: they fire action potentials (electrical spikes) only when membrane potential exceeds threshold, remaining silent otherwise—an event-driven paradigm where energy scales with activity rather than clock speed. Studies of cortical neurons find average firing rates of 0.1-10 Hz (spikes per second), far below the gigahertz switching frequencies of digital circuits, with neurons spending >99% of time in low-power idle states between spikes. Neuromorphic systems adopt this event-driven approach, activating computational units only when events (incoming spikes) occur—achieving energy proportional to useful work rather than wasting power on synchronization.

Analog versus digital computation represents a third design choice with efficiency implications. Digital circuits represent information with discrete voltage levels (0V = logical 0, 1V = logical 1), requiring energy-intensive voltage swings and noise-resistant signal regeneration at every logic gate. Biological neurons use analog membrane potentials that vary continuously, with computation emerging from electrochemical dynamics rather than discrete logic operations. Analog computation is inherently more energy-efficient for certain operations (a single capacitor integrating charge performs summation at femtojoule energy scales versus picojoule-scale digital addition), though it sacrifices precision—analog systems typically achieve 8-10 bits effective resolution versus 32-bit or 64-bit precision in digital arithmetic. For AI inference where moderate precision suffices (research shows many neural networks tolerate 8-bit or even 4-bit quantization with minimal accuracy loss), analog computation offers attractive energy-accuracy tradeoffs that neuromorphic architectures exploit.

Learning versus reprogramming constitutes the final difference. Updating conventional AI models requires transferring gigabytes of weights from training servers to deployment devices, then swapping model parameters in memory—an expensive operation necessitating versioning, validation, and often device restart. Biological brains learn continuously through synaptic plasticity: connection strengths between neurons adjust based on correlated activity patterns, implementing learning rules like spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) where synapses strengthen if pre-synaptic spikes consistently precede post-synaptic spikes. Neuromorphic systems implement on-chip learning through configurable plasticity rules, enabling devices to adapt to new environments without external training loops—critical capability for applications like personalized medical devices or autonomous robots in unpredictable environments.

Neuromorphic Hardware Architectures: From Spiking Neurons to Silicon

Neuromorphic computing encompasses diverse hardware approaches varying in biological realism, scalability, and programmability. Leading research systems demonstrate different design philosophies addressing the tradeoffs between brain-like operation and practical engineering constraints.

Intel’s Loihi 2, introduced in 2021 and deployed in research partnerships since 2023, contains 1 million spiking neurons and 120 million synapses fabricated in Intel 4 process technology (7nm equivalent). The architecture implements leaky integrate-and-fire neurons: each neuron maintains membrane potential that increases when receiving excitatory input spikes, decreases via leaky decay over time, and fires output spike when potential exceeds threshold—mathematical model approximating biological neuron dynamics. Synapses feature programmable weights (connection strengths) and delays (transmission latency between neurons), with learning rules including STDP and reward-modulated plasticity implemented in on-chip circuits. Loihi 2 improves upon the original Loihi (2017) with 10× larger neuron count, graded spikes (spike amplitude carries information beyond binary fire/no-fire), configurable neuron dynamics (supporting multiple neuron models from simple to biologically detailed), and improved programmability through embedded x86 cores enabling hybrid neuromorphic-conventional processing. Power efficiency reaches 2,000× better than GPUs for specific sparse event-driven workloads like continuous learning, gesture recognition from event-based cameras, and constraint satisfaction optimization.

IBM’s TrueNorth, pioneered in 2014, took a different architectural approach prioritizing scalability and low power. Each TrueNorth chip contains 1 million neurons and 256 million synapses organized as 4,096 neurosynaptic cores operating independently with no shared memory—radically parallel architecture eliminating communication bottlenecks. The system consumes 70 milliwatts at typical workloads (equivalent to a hearing aid battery), enabling always-on inference for mobile and IoT applications. However, TrueNorth uses simplified neuron models and binary synapses (1-bit weights) limiting representational capacity compared to Loihi’s higher precision—reflecting tradeoff between biological realism and scalability. IBM demonstrated TrueNorth systems with up to 64 million neurons (built from 64 chips) for applications including real-time image classification, vibration-based structural health monitoring, and keyword spotting in audio streams—domains where ultra-low power and continuous operation justify accepting limitations in model expressiveness. TrueNorth development has since concluded, with IBM focusing on conventional AI accelerators, though the architecture influenced neuromorphic research directions.

![]()

BrainScaleS-2, developed by Heidelberg University, pursues extreme biological realism through analog circuits emulating neuron and synapse biophysics with microsecond timescale accuracy—enabling neuroscience research on brain mechanisms. The system implements adaptive exponential integrate-and-fire neurons with conductance-based synapses (modeling ion channel dynamics), configurable through on-chip plasticity processors. BrainScaleS-2’s unique capability is accelerated-time emulation: analog circuits operate 1,000× faster than biological real-time, simulating one second of biological neural activity in one millisecond of wall-clock time—enabling rapid exploration of neural dynamics and learning rules. However, analog circuits suffer from manufacturing variability (no two neurons behave identically due to transistor mismatch) and limited scale (current system contains 512 neurons per chip, far below Loihi’s million-neuron count), restricting applications primarily to neuroscience research rather than production AI workloads. The system has contributed insights into biological learning mechanisms including local plasticity rules sufficient for supervised learning and self-organization of receptive fields from sensory input.

SpiNNaker2, successor to the pioneering SpiNNaker project at University of Manchester, takes a digital approach implementing spiking neural networks on custom many-core processors. Each SpiNNaker2 chip contains 152 ARM cores interconnected with asynchronous network-on-chip, running neuron simulations in software rather than fixed analog circuits—providing maximum flexibility to implement arbitrary neuron models and learning rules at the cost of higher power consumption than analog neuromorphic chips. The architecture excels at large-scale brain simulations: a SpiNNaker2 machine with 600 chips can simulate 10 billion neurons in biological real-time, enabling whole-brain modeling of small mammals. Applications focus on computational neuroscience (testing theories of cortical function, hippocampal memory, cerebellum motor control) and neural network architecture search (rapidly prototyping and evaluating novel spiking network designs). Power efficiency falls between conventional GPUs and analog neuromorphic chips—approximately 10× better than GPUs but 10× worse than TrueNorth—reflecting software flexibility versus hardware specialization tradeoff.

Memristor-based neuromorphic systems represent an emerging approach using novel memory devices with resistance that changes based on historical current flow—analog to synaptic plasticity where connection strength depends on activity history. Crossbar arrays of memristors implement neural network weight matrices with one device per synapse, enabling massively parallel analog matrix-vector multiplication at extremely high density (billions of synapses per square centimeter). IBM, HP Labs, and startups like Rain Neuromorphics have demonstrated memristor neural networks achieving 100-1,000× better energy efficiency than GPUs for inference, with in-situ training through gradual memristor programming. However, memristors suffer from device-to-device variability, drift (resistance changing unpredictably over time), and limited endurance (devices wear out after 10^6-10^9 write cycles)—reliability challenges that have prevented commercial deployment despite promising demonstrations. Ongoing research addresses variability through error-correction techniques and drift through periodic recalibration, with optimists predicting production memristor AI accelerators by 2025-2027 while skeptics question whether memristor reliability will ever match silicon transistor maturity.

Applications and Use Cases: Where Neuromorphic Computing Excels

Neuromorphic hardware is not universally superior to conventional accelerators—rather, it excels in specific application domains where event-driven processing, continuous operation, and energy constraints align with neuromorphic strengths.

Event-based sensing and edge AI represent neuromorphic computing’s most natural applications. Event cameras (neuromorphic vision sensors) output pixel-level brightness changes only when changes occur, rather than capturing full frames at fixed rates—matching neuromorphic processors’ event-driven operation. The combination enables vision systems consuming microwatts to milliwatts: iniVation’s DAVIS event camera paired with Loihi chip achieved gesture recognition at 3 milliwatts total system power (100× more efficient than conventional camera+GPU), enabling always-on vision for battery-powered devices like security cameras, AR glasses, and drone navigation. Event-based processing particularly excels for motion detection and tracking where only moving objects generate events, versus conventional vision that processes entire frames including static background. Research from Delft University demonstrated robotic visual servoing (using vision to guide robot arm movements) with 1 millisecond latency using event camera + neuromorphic processor—10× faster than conventional vision pipeline bottlenecked by frame rate, enabling robots to catch thrown objects and compensate for vibrations that conventional control systems cannot react to quickly enough.

Continuous learning and personalization leverage neuromorphic chips’ on-chip plasticity mechanisms. Medical devices like neural implants or prosthetic limbs must adapt to individual users’ neural patterns that vary between patients and drift over time—requiring on-device learning without external training infrastructure. Intel Research demonstrated Loihi-powered myoelectric prosthetic control that improved accuracy from 73% (initial factory-trained model) to 94% (personalized after 20 minutes user interaction) through STDP-based online learning. The system adapted to user’s muscle activation patterns and learned to reject motion artifacts (false signals from limb movement rather than intentional muscle contractions) through correlated activity detection—achieving personalization that conventional implants cannot match without risky wireless connectivity enabling cloud-based retraining. Similar applications include brain-computer interfaces translating neural signals to computer commands, hearing aids adapting to acoustic environments, and wearable health monitors learning individual baseline physiology for anomaly detection.

Optimization and constraint satisfaction problems map naturally onto spiking neural networks through energy-based formulations. Hopfield networks and Boltzmann machines—neural network architectures predating modern deep learning—solve optimization by encoding problem constraints in connection weights, then relaxing the network to stable states representing solutions. Neuromorphic implementations leverage asynchronous parallel updates enabling networks to explore solution spaces efficiently. Sandia National Laboratories demonstrated vehicle routing optimization (finding efficient paths for delivery fleets) on Loihi achieving solutions within 2% of optimal in 50 milliseconds while consuming 15 milliwatts—performance matching conventional solvers but at 100× lower power, enabling optimization on mobile robots or drones selecting paths autonomously without communication overhead. Other demonstrations include job shop scheduling, protein folding pathways, and radio spectrum allocation—combinatorial optimization problems where neuromorphic speedup and efficiency enable real-time optimization for control systems.

Anomaly detection and rare event recognition benefit from neuromorphic systems’ ability to process continuous data streams efficiently while remaining sensitive to unusual patterns. Structural health monitoring for bridges, aircraft, and industrial equipment involves analyzing vibration sensor data continuously to detect anomalies indicating damage or wear—needles in haystacks buried in gigabytes of normal operation data. IBM demonstrated TrueNorth-based vibration monitoring consuming 2 watts while analyzing 32 channels of high-frequency accelerometer data in real-time, detecting bearing failures 48 hours before catastrophic breakdown with 97% sensitivity and less than 1% false positive rate—matching conventional machine learning systems but at 50× lower power enabling years-long deployment on battery power where GPU-based systems would require mains electricity or frequent battery replacement. Similar applications include network intrusion detection (identifying cyberattacks in network traffic), environmental monitoring (detecting pollution spikes or wildlife activity from acoustic sensors), and preventive maintenance (predicting equipment failures from operational telemetry).

Keyword spotting and always-on voice interfaces require continuously processing audio to detect activation phrases (“Hey Siri,” “OK Google”) while minimizing power consumption—smartphones cannot afford to run speech recognition models continuously at multi-watt power levels draining batteries in hours. BrainChip’s Akida neuromorphic processor implements keyword spotting at 6 milliwatts, enabling always-listening voice interfaces that run for months on coin cell batteries. The system uses temporal coding (precise timing of spikes carries information about audio features) and recurrent connectivity (feedback loops process temporal sequences) to recognize speech patterns, achieving 93% accuracy matching conventional keyword spotting models but at 100× lower power by exploiting sparsity—audio contains silent periods and frequency bands where no energy appears, generating zero spikes and consuming zero power in neuromorphic implementation versus continuous computation in conventional systems. Applications extend beyond smartphones to hearing aids, smart home devices, industrial voice control, and accessibility tools where battery life critically constrains deployment.

Challenges and Limitations: The Road to Mainstream Adoption

Despite promising demonstrations, neuromorphic computing faces significant technical, software, and ecosystem challenges that have prevented widespread commercial adoption 12+ years after pioneering systems like TrueNorth and SpiNNaker emerged.

Software and programming models remain immature compared to conventional deep learning frameworks. Training spiking neural networks requires specialized algorithms (surrogate gradient methods, evolutionary strategies, or converting pre-trained conventional networks to spiking equivalents) that lack the maturity, documentation, and tooling of TensorFlow/PyTorch ecosystem. Developers must learn new programming paradigms (event-driven computation, temporal coding, asynchronous communication) that differ fundamentally from conventional batch processing—steep learning curve limiting neuromorphic adoption to specialists. Intel provides Lava, an open-source framework for Loihi programming, but the ecosystem of pre-trained models, tutorials, and community support remains minuscule compared to conventional deep learning. This software gap means that even when neuromorphic hardware offers superior efficiency, most developers cannot leverage it without substantial investment learning unfamiliar tools—creating chicken-and-egg problem where limited adoption justifies limited tooling investment, perpetuating adoption barriers.

Benchmark and standardization challenges make comparing neuromorphic systems to conventional approaches difficult. Conventional AI uses standardized benchmarks (ImageNet for vision, GLUE for language) and metrics (accuracy, throughput, latency, power) enabling apples-to-apples comparisons. Neuromorphic systems lack equivalent standards: papers report different metrics (energy per inference, energy-delay product, spikes per classification), use different workloads (often chosen to showcase neuromorphic strengths), and sometimes compare to inefficient conventional baselines (CPUs rather than optimized GPU or mobile accelerator implementations). A 2023 review in Nature Electronics analyzing 47 neuromorphic research papers found that only 23% compared to state-of-the-art conventional implementations, and among those, 67% showed neuromorphic advantages only for specific operating points (particular latency targets or batch sizes) rather than across application space. Establishing credible, representative benchmarks remains critical for validating neuromorphic claims and guiding research toward commercially relevant applications.

Limited scale and ecosystem lock-in restrict deployment options. Intel’s Loihi 2 contains 1 million neurons—orders of magnitude smaller than billion-parameter deep learning models dominating AI benchmarks and applications. While brain-inspired sparsity and temporal coding can achieve impressive results with fewer neurons, fundamental questions remain about whether neuromorphic approaches can scale to large language models, computer vision systems, or recommender models that have driven recent AI progress. Neuromorphic advocates argue that entirely different network architectures (recurrent rather than feedforward, event-driven rather than batch-processed) will enable scaling—but this remains empirically unvalidated. Additionally, each neuromorphic platform uses proprietary programming models, making applications non-portable: code for Loihi doesn’t run on TrueNorth or BrainScaleS, creating vendor lock-in and fragmentation versus conventional AI’s standardized CUDA/cuDNN enabling GPU portability across NVIDIA, AMD, and emerging accelerators.

Analog circuit challenges affect neuromorphic systems using analog computation for efficiency. Analog circuits suffer from noise (thermal fluctuations, interference), variability (manufacturing imperfections causing device-to-device differences), and sensitivity to environmental conditions (temperature, voltage fluctuations affect behavior). Digital circuits achieve reliability through error correction, redundancy, and noise-resistant signaling—techniques that analog systems cannot easily apply. Research shows that memristor neural networks require 20-30% overprovisioning (extra devices for error correction) to match digital reliability, significantly eroding density and efficiency advantages. Aging and drift (device characteristics changing over months-years of operation) pose additional concerns for long-lived deployments: will neuromorphic implants maintain accuracy after 10 years in the human body? Digital systems use error-correcting memory and periodic validation to ensure correctness, while analog neuromorphic systems lack equivalent mechanisms—creating liability concerns for safety-critical applications.

Application-specific versus general-purpose tradeoffs mean neuromorphic chips excel narrowly but struggle broadly. Loihi achieves 1,000× efficiency gains for specific event-driven sparse workloads but shows minimal advantage (or even worse performance) for dense matrix operations, batch inference, or training large models—workloads dominating production AI systems. Data centers running diverse workloads (computer vision, language models, recommendation, speech recognition, search ranking) prefer general-purpose accelerators handling all tasks efficiently over specialized accelerators excelling narrowly. Unless neuromorphic advantages justify dedicated hardware for specific applications (e.g., ultra-low-power edge devices where battery life is critical), conventional accelerators’ versatility will continue dominating. The economic question is whether sufficiently large markets exist for neuromorphic-specific applications (billions of IoT sensors? millions of autonomous robots?) to justify ecosystem investment.

The Future of Neuromorphic Computing: Integration and Coexistence

Rather than replacing conventional computing, neuromorphic systems will likely coexist in heterogeneous architectures where each technology addresses workloads matching its strengths—analogous to how GPUs augment CPUs rather than replacing them entirely.

Hybrid neuromorphic-conventional architectures combine technologies synergistically. Intel’s Loihi 2 integrates x86 cores alongside neuromorphic tiles, enabling conventional code to preprocess data, control neuromorphic execution, and post-process results—best-of-both-worlds approach where neuromorphic fabric handles event-driven inference while conventional cores manage irregular control flow and legacy code. Similarly, research systems pair event cameras (producing spike trains naturally matching neuromorphic input) with conventional cameras (providing high-fidelity frames when needed), selecting sensing modality based on task requirements and power budget. Future smartphones might include neuromorphic coprocessors for always-on keyword spotting and sensor processing, activating power-hungry GPUs only when neuromorphic preprocessor detects events warranting full analysis—tiered compute matching precision and energy to task requirements.

Neuromorphic for edge, conventional for cloud divides AI deployment across infrastructure tiers. Edge devices (sensors, wearables, robots) prioritize power efficiency and real-time response, favoring neuromorphic implementations processing local data continuously at milliwatt power levels. Cloud services prioritize throughput and versatility, running conventional accelerators that batch-process data from thousands of edge devices, perform complex reasoning requiring large models, and train updated models deployed to edge—division of labor exploiting each technology’s comparative advantage. This architecture also enhances privacy (sensitive data processed locally on neuromorphic edge devices never leaves user control) and reduces bandwidth (only high-level features or anomalies transmit to cloud rather than raw sensor streams), providing benefits beyond pure efficiency.

Standardization and abstraction layers will mature, insulating developers from hardware details. Just as CUDA enabled GPU programming without understanding memory hierarchies and thread scheduling, higher-level abstractions can hide neuromorphic complexity. Emerging frameworks like Nengo and Brian provide hardware-agnostic spiking neural network programming, compiling to Loihi, SpiNNaker, GPUs, or CPU backends—enabling developers to write once, deploy anywhere. As these tools mature and pre-trained spiking models become available (analogous to how Hugging Face hosts thousands of conventional models), neuromorphic adoption barriers will decline. Hardware-software co-design will produce domain-specific architectures optimized for particular applications (automotive perception, medical implants, industrial monitoring) with specialized toolchains hiding generic neuromorphic programming complexity—lowering expertise requirements from neuromorphic specialists to conventional embedded developers.

Biologically inspired learning algorithms may prove neuromorphic computing’s most enduring contribution even if specialized hardware adoption remains niche. Techniques like STDP, online continual learning, and temporal credit assignment developed for neuromorphic systems have influenced conventional AI research, inspiring gradient-based analogs of biological plasticity and recurrent architectures processing temporal sequences efficiently. If these algorithms prove superior for specific tasks (few-shot learning, lifelong learning, robustness), they’ll be adopted in conventional AI regardless of neuromorphic hardware success—analogous to how backpropagation (inspired by theories of biological learning) became conventional AI’s workhorse despite limited biological realism.

Conclusion and Strategic Outlook

Neuromorphic computing represents a paradigm shift in AI hardware, replacing conventional architectures’ clock-driven synchronous operation with event-driven asynchronous processing mimicking biological neural networks. Key insights include:

- Energy efficiency advantages: Intel Loihi 2 achieved 100× better power efficiency than GPUs for event-driven workloads, consuming 140 milliwatts for robotic control versus multi-watt conventional implementations

- Biological realism trade-offs: Architectures range from highly abstract (TrueNorth’s simplified neurons) to biophysically detailed (BrainScaleS analog circuits), balancing realism against scalability and reliability

- Application-specific strengths: Neuromorphic excels for event-based sensing, continuous learning, optimization, and anomaly detection—not universal AI replacement but specialized capability

- Maturity challenges: Software ecosystem, benchmarks, and scale lag conventional AI by 5-10 years, preventing mainstream adoption despite 12+ years research investment

- Coexistence trajectory: Future systems will hybridize neuromorphic and conventional approaches, deploying each where comparative advantages justify specialized hardware

Organizations developing ultra-low-power edge AI (IoT sensors, wearables, autonomous systems) should monitor neuromorphic progress and experiment with available platforms—Intel’s Loihi cloud access enables exploration without hardware investment. However, those focused on cloud AI, training large models, or general-purpose inference should continue conventional accelerators where maturity and ecosystem justify investment. The neuromorphic vision of ubiquitous intelligence in every device—billions of edge sensors processing locally at microwatt power—remains compelling, but realizing this vision requires overcoming software immaturity, standardization gaps, and economic questions about application-specific hardware versus versatile conventional alternatives. The next 3-5 years will determine whether neuromorphic computing achieves mainstream adoption or remains a research niche with specialized applications.

Sources

- Davies, M., et al. (2021). Advancing neuromorphic computing with Loihi: A survey of results and outlook. Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(5), 911-934. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2021.3067593

- Merolla, P. A., et al. (2014). A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science, 345(6197), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254642

- Roy, K., Jaiswal, A., & Panda, P. (2019). Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature, 575, 607-617. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1677-2

- Schuman, C. D., et al. (2022). Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nature Computational Science, 2, 10-19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-021-00184-y

- Indiveri, G., & Liu, S. C. (2015). Memory and information processing in neuromorphic systems. Proceedings of the IEEE, 103(8), 1379-1397. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2015.2444094

- Christensen, D. V., et al. (2022). 2022 roadmap on neuromorphic computing and engineering. Neuromorphic Computing and Engineering, 2(2), 022501. https://doi.org/10.1088/2634-4386/ac4a83

- Frenkel, C., Legat, J. D., & Bol, D. (2019). MorphIC: A 65-nm 738k-synapse/mm² quad-core binary-weight digital neuromorphic processor with stochastic spike-driven online learning. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems, 13(5), 999-1010. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBCAS.2019.2928793

- Ielmini, D., & Wong, H. S. P. (2018). In-memory computing with resistive switching devices. Nature Electronics, 1, 333-343. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-018-0092-2

- Sorbaro, M., et al. (2020). Optimizing the energy consumption of spiking neural networks for neuromorphic applications. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 662. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00662