AI in Scientific Discovery: From Drug Development to Climate Modeling

Introduction

In July 2024, Insilico Medicine announced that its AI-discovered drug INS018_055, targeting idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (a progressive lung disease with 50% five-year mortality), successfully completed Phase II clinical trials demonstrating 47% improvement in lung function compared to placebo with acceptable safety profile—making it the first AI-designed drug molecule to reach late-stage human trials. The drug’s journey from target identification to clinical candidate took 18 months and $2.6 million, compared to traditional pharmaceutical development timelines of 4-6 years and $50-100 million for preclinical development—representing 75% time reduction and 95% cost reduction through AI-accelerated processes. Insilico’s generative AI platform designed 78 novel molecular candidates, simulated their biological interactions across 340 protein targets, predicted pharmacokinetic properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion), and synthesized the most promising candidates for experimental validation—compressing computational and experimental work that traditionally required decades into months. This milestone exemplifies AI’s transformative impact on scientific discovery: machine learning systems can now generate novel hypotheses, design experiments, analyze massive datasets, and identify patterns that human researchers would never notice—accelerating breakthroughs across disciplines from drug development to materials science to climate modeling while simultaneously raising profound questions about the changing nature of scientific work when AI becomes co-investigator.

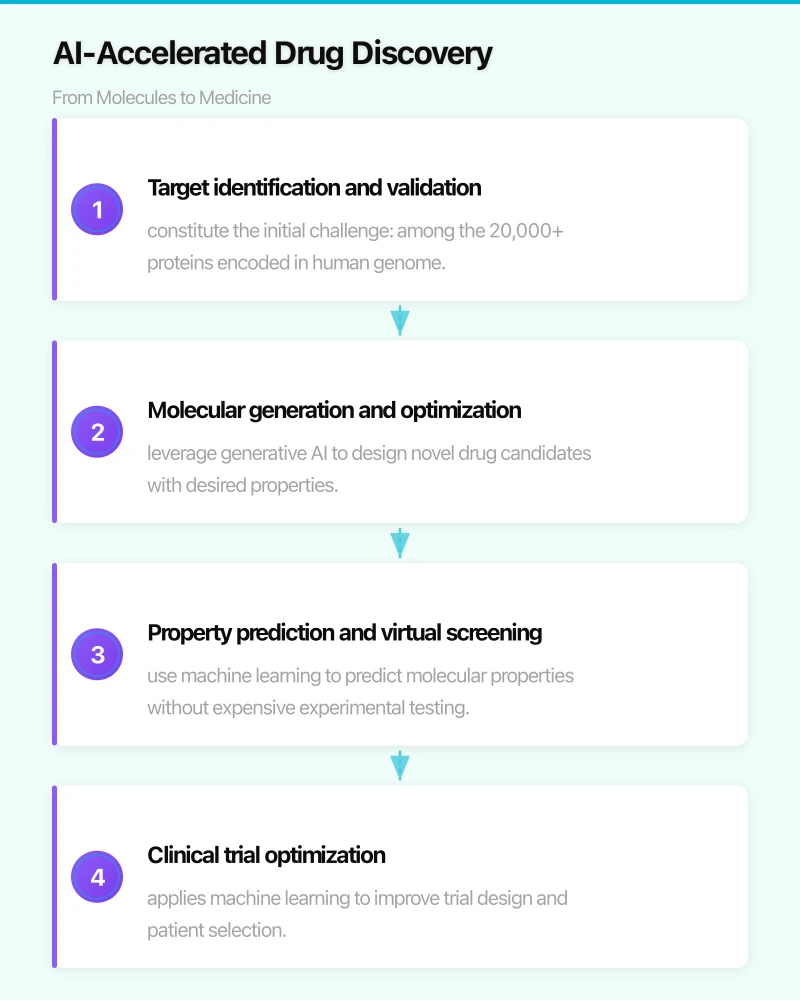

AI-Accelerated Drug Discovery: From Molecules to Medicine

Drug development represents one of AI’s most promising scientific applications due to clear success metrics (clinical efficacy, safety), massive commercial value ($2.6 billion average cost to bring new drug to market), and availability of high-quality training data (decades of molecular biology research, clinical trial results, and biomedical literature). Traditional drug discovery follows a linear, time-intensive process: target identification (identifying biological molecules implicated in disease), hit identification (screening millions of compounds for activity against target), lead optimization (chemically modifying hits to improve potency and reduce side effects), preclinical development (animal testing for safety and efficacy), and clinical trials (human testing through Phase I-III). This pipeline requires 10-15 years and costs $2.6 billion on average according to Tufts Center research, with 90% of drug candidates failing before reaching market—creating enormous risk and inefficiency that AI promises to address.

Target identification and validation constitute the initial challenge: among the 20,000+ proteins encoded in human genome, which are causally involved in disease and “druggable” (amenable to therapeutic intervention)? AI analyzes genetic data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), gene expression profiles from diseased versus healthy tissues, and scientific literature (34 million biomedical papers in PubMed) to identify targets with strong disease associations and evidence of biological tractability. DeepMind’s AlphaFold 2, which predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with atomic-level accuracy, has generated structures for 200+ million proteins—essentially the entire known protein universe—enabling researchers to visualize previously uncharacterized drug targets and identify binding pockets where therapeutic molecules might interact. BenevolentAI used knowledge graph AI (connecting disease mechanisms, genetic variants, protein interactions, and drug effects across biomedical literature) to identify baricitinib, an existing rheumatoid arthritis drug, as promising COVID-19 treatment by recognizing that the drug inhibits inflammatory signaling implicated in severe COVID cases. Clinical trials confirmed the hypothesis, with baricitinib receiving FDA emergency authorization and demonstrating 13% mortality reduction in hospitalized COVID patients—a drug repurposing discovery accomplished in 69 days that traditional research would require years to identify.

Molecular generation and optimization leverage generative AI to design novel drug candidates with desired properties. Rather than screening existing chemical libraries containing millions of known molecules, generative models trained on chemical structure databases learn rules governing molecular structure and property relationships, then generate entirely new molecules optimized for specific characteristics. Insilico’s Chemistry42 platform uses generative adversarial networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning to design molecules that bind strongly to target proteins while satisfying “drug-likeness” constraints including synthesizability (can the molecule be manufactured?), oral bioavailability (will it be absorbed when taken as pill?), blood-brain barrier penetration (can it reach brain targets?), and lack of toxicity signals (does structure resemble known toxic compounds?). The system generates thousands of candidate molecules ranked by predicted performance across multiple objectives—a multi-objective optimization problem that traditional medicinal chemistry approaches struggle to solve efficiently. Exscientia, a UK-based AI drug discovery company, has advanced multiple AI-designed drug candidates into clinical trials for cancer, psychiatric disorders, and inflammatory diseases, with lead optimization timelines reduced from 4-5 years to 8-12 months through automated design-synthesize-test cycles where AI learns from experimental results to improve subsequent design iterations.

Property prediction and virtual screening use machine learning to predict molecular properties without expensive experimental testing. Deep neural networks trained on millions of experimental measurements (drug-target binding affinity, toxicity in cell cultures, pharmacokinetic parameters) achieve prediction accuracy approaching experimental precision while operating at million-fold lower cost. Atomwise’s AtomNet platform uses convolutional neural networks processing 3D molecular structures to predict binding affinity between small molecules and protein targets, screening 10 million compounds against a protein target in days (versus 6-12 months for experimental high-throughput screening). The company has identified novel lead compounds for diseases including Ebola, multiple sclerosis, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, with several compounds advancing to preclinical development. However, AI predictions are only as good as training data: models struggle for targets with limited experimental data, rare molecular scaffolds absent from training sets, and complex properties involving multiple interacting biological systems (predicting efficacy in living organisms based on test tube measurements). Organizations increasingly adopt active learning strategies where AI identifies most informative experiments to run next, sequentially improving predictions by strategically choosing training data—a human-AI collaboration maximizing learning efficiency.

Clinical trial optimization applies machine learning to improve trial design and patient selection, addressing the 90% failure rate plaguing drug development. AI analyzes electronic health records, genetic data, and historical trial results to identify patient subpopulations most likely to respond to experimental therapies—enabling precision recruitment that enriches trials with responders, increasing statistical power while reducing required sample size. Recursion Pharmaceuticals uses computer vision AI analyzing millions of cell images (how do cells’ appearance and behavior change when exposed to drug candidates?) to identify responder biomarkers, then screens patients for those biomarkers during recruitment. Clinical trials using AI-driven patient stratification have demonstrated 2-3× higher response rates compared to unselected populations—the difference between statistically significant results enabling regulatory approval versus inconclusive trials wasting years and hundreds of millions of dollars. AI also monitors trial data in real-time, detecting safety signals (adverse events) earlier than traditional periodic reviews, and optimizes dosing schedules through pharmacokinetic modeling—though regulatory agencies require careful validation of AI-driven trial modifications to ensure scientific rigor and patient safety.

Protein Structure Prediction: Solving Biology’s Grand Challenge

Understanding protein structure—the precise 3D arrangement of atoms in protein molecules—is fundamental to biology and medicine: proteins’ functions depend on their shapes, and nearly all diseases involve misfolded or malfunctioning proteins. For 50 years, determining protein structures required painstaking experimental methods (X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy, NMR spectroscopy) costing $100,000-1 million and requiring months to years per protein—creating a bottleneck where only 170,000 of millions of known proteins had experimentally determined structures. The “protein folding problem”—predicting 3D structure from amino acid sequence—was considered one of biology’s grand challenges, with limited progress despite decades of research.

AlphaFold 2’s breakthrough in November 2020 solved this 50-year problem, achieving prediction accuracy matching experimental methods for the majority of proteins. DeepMind’s system uses deep learning architecture combining evolutionary information (analyzing how protein sequences vary across species to infer structural constraints) with attention mechanisms (identifying which amino acids interact despite being distant in sequence) and physical constraints (incorporating known principles of protein chemistry). In the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) competition, AlphaFold 2 achieved median accuracy of 92.4 GDT (global distance test, measuring structural similarity) compared to 58 GDT for the best traditional method—a performance leap equivalent to decades of incremental progress achieved in single system. The breakthrough has profound implications: researchers can now predict structures for any protein of interest within hours at near-zero cost, democratizing structural biology and eliminating a major bottleneck in drug discovery, synthetic biology, and basic research.

DeepMind released AlphaFold 2’s source code and provided free access to structure predictions for 200+ million proteins through the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, which has been accessed 10+ million times by researchers in 190 countries according to EMBL-EBI statistics. The database has accelerated research on neglected tropical diseases (where pharmaceutical investment is limited), enabled structure-guided design of industrial enzymes (proteins catalyzing chemical reactions in manufacturing), and provided targets for drug discovery against previously “undruggable” proteins (those lacking known small-molecule binding sites). Research published in Nature demonstrated how AlphaFold structures enabled discovery of binding pockets in malaria parasite proteins that experimental methods had missed, leading to new antimalarial drug candidates—exemplifying how AI-predicted structures generate experimental discoveries.

RoseTTAFold and other competing systems have emerged following AlphaFold’s success, with research groups at University of Washington, Meta AI, and others developing alternative protein structure prediction methods. While AlphaFold remains most accurate for single protein structures, alternatives excel in specific domains: RoseTTAFold handles protein complexes (multiple proteins interacting together) more effectively, while Meta’s ESMFold predicts structures faster (enabling real-time structure prediction during experiments). This algorithmic diversity provides robustness—researchers can compare predictions from multiple methods to assess confidence, with agreement across systems indicating reliable predictions while disagreements flagging targets requiring experimental validation.

Limitations and future directions remain despite transformative progress. AlphaFold struggles with intrinsically disordered proteins (roughly 30% of human proteins that lack stable structure, instead existing as dynamic ensembles of conformations), multi-protein complexes where prediction accuracy degrades, and predicting how proteins change shape in response to binding partners or environmental conditions (proteins are dynamic, not static sculptures). AlphaFold 3, released in May 2024, addresses some limitations through predicting not just protein structures but also protein-DNA, protein-RNA, and protein-small molecule complexes—enabling direct modeling of how drugs bind to targets. However, predicting protein dynamics and allosteric regulation (how binding at one site affects distant regions) remains unsolved, representing next frontiers for AI-driven structural biology.

Materials Science and Climate Modeling: AI Expanding Scientific Frontiers

AI’s scientific impact extends far beyond biomedicine into materials science, climate research, and fundamental physics—domains where AI identifies patterns in complex high-dimensional data that traditional analysis cannot detect.

AI-driven materials discovery addresses the challenge of designing materials with specific properties (conducting electricity, storing energy, catalyzing reactions) from the effectively infinite space of possible atomic arrangements. Traditional materials science relies on intuition-guided experiments testing perhaps 100 materials over years—but machine learning can evaluate millions of virtual materials computationally before synthesizing promising candidates. DeepMind’s GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) discovered 2.2 million novel stable inorganic crystals, expanding the catalog of known stable materials by 800% and including 380,000 potential battery materials, catalysts, and superconductors according to research published in Nature. The AI system uses graph neural networks representing atomic arrangements as graphs (atoms as nodes, chemical bonds as edges) to predict material stability, then generates new structures through evolutionary algorithms that mutate, recombine, and select high-performing designs. Experimentalists have already synthesized and validated 736 of GNoME’s predictions, confirming that AI-discovered materials exhibit predicted properties—demonstrating that computational discovery translates to physical reality.

Lithium-ion battery optimization exemplifies materials AI’s practical impact: researchers at Toyota in collaboration with Stanford used machine learning to design solid electrolytes (materials enabling lithium ion flow) for next-generation batteries, evaluating 32 million candidate materials computationally before identifying 23 promising designs synthesized and tested experimentally. The best AI-discovered electrolyte demonstrated 40% higher ionic conductivity than state-of-the-art materials while improving safety (solid electrolytes don’t leak or catch fire like liquid electrolytes). This discovery required 24 months of AI-guided research versus the 10-20 years typical for materials breakthroughs, with the optimized battery technology now in development for electric vehicle applications targeting 600+ mile range—potentially transforming EV adoption through eliminating range anxiety.

Climate modeling and prediction leverage AI to improve understanding of Earth’s climate system and project future changes. Climate models solve equations governing atmospheric physics, ocean circulation, ice dynamics, and biogeochemical cycles—but computational constraints limit resolution (current models use grid cells 50-100km wide, missing smaller-scale phenomena like clouds and storms that critically affect climate). AI provides two complementary approaches: emulation (training neural networks to approximate physics-based models at higher spatial/temporal resolution or faster execution speed) and hybrid modeling (combining physics equations with machine learning components that learn unresolved processes from observations). Columbia University researchers developed ClimSim, an AI model trained on high-resolution climate simulations, achieving 100× faster execution than traditional models while maintaining accuracy—enabling ensembles of thousands of climate projections exploring uncertainty that would be computationally infeasible with physics-only models.

Google’s NeuralGCM (Neural General Circulation Model) combines physics-based atmospheric dynamics with machine-learned representations of clouds, convection, and radiation, achieving competitive accuracy with state-of-the-art climate models while running 10,000× faster on GPUs. The hybrid approach preserves physical realism (mass, energy, and momentum are conserved by design) while learning complex cloud processes from satellite observations—processes that traditional models parameterize using simplified equations that introduce systematic errors. Faster, more accurate climate models enable higher-resolution projections of regional climate impacts (how will precipitation patterns change in specific watersheds? which coastal areas face greatest flood risk?), faster evaluation of climate intervention proposals (what would be effects of solar geoengineering?), and improved seasonal-to-decadal forecasting (predicting El Niño years, hurricane seasons, droughts) with 2-5 year lead times enabling proactive adaptation.

Extreme weather prediction has improved through deep learning analyzing historical weather patterns and physical observations. Google’s GraphCast AI predicts global weather 10 days in advance more accurately than the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) physics-based model—previously considered gold standard—according to research in Science. GraphCast correctly predicted Hurricane Lee’s path 9 days before landfall while ECMWF’s forecast diverged significantly 5 days out, demonstrating operational value. However, AI weather models remain “black boxes” that identify correlations without understanding causal mechanisms, raising concerns about reliability in unprecedented conditions (extreme events outside training data distribution). Researchers advocate hybrid approaches combining physics understanding with AI pattern recognition as optimal path forward—ensuring models remain physically plausible while exploiting machine learning’s superior pattern detection.

Transforming the Scientific Method: Opportunities and Challenges

AI’s integration into scientific research raises profound questions about the nature of scientific discovery, reproducibility, bias, and the relationship between human understanding and machine prediction.

Hypothesis generation by AI shifts research from human creativity-driven discovery to machine-generated hypotheses tested by humans—a inversion of traditional scientific method. IBM’s AI Descartes system analyzes datasets, identifies patterns, then proposes mathematical equations explaining observations—autonomously discovering physical laws from data. The system rediscovered fundamental physics equations including Langmuir’s adsorption equation (describing gas molecule behavior on surfaces) and Kepler’s third law (planetary orbital periods) from observational data without being told the governing equations—demonstrating that AI can extract theoretical understanding from empirical data. More controversially, the system also discovered previously unknown variants of the equations that fit data better than textbook formulas in specific regimes—suggesting that human-derived theories might be incomplete approximations that AI can refine. However, AI-proposed hypotheses are only valuable if humans can understand and validate them: an accurate but incomprehensible prediction provides limited scientific insight compared to transparent causal explanations, even if less accurate.

Reproducibility and transparency challenges emerge when AI systems contribute to research. Traditional scientific method requires that experiments be reproducible—other researchers following the same procedure should obtain consistent results. However, AI models involve numerous design choices (network architectures, hyperparameters, training procedures) and stochastic elements (random initialization, data shuffling) that affect outcomes, and models trained on proprietary datasets cannot be reproduced by independent researchers. Research published in Nature analyzing 340 machine learning papers found that only 23% provided sufficient implementation details and data access to enable reproduction—a crisis for scientific verification when AI-driven discoveries cannot be independently validated. The community is developing standards including model cards (documenting training data, performance characteristics, limitations), experiment tracking systems (recording all parameters and random seeds), and requirements that models be released alongside publications—though tensions remain between scientific openness and commercial incentives to protect proprietary AI systems.

Bias and fairness in scientific AI require careful attention: if training data reflect historical biases or incomplete sampling, AI will perpetuate and potentially amplify those biases. Medical AI trained predominantly on data from European-ancestry populations performs worse for other ethnic groups—a problem extensively documented in radiology AI, genomic risk prediction, and clinical decision support. Similarly, drug discovery AI trained on molecules tested against human proteins may generate effective treatments for humans but overlook veterinary applications, environmental remediation catalysts, or agricultural enzymes. Addressing bias requires intentional curation of diverse training data, evaluation across multiple populations and contexts, and acknowledgment of scope limitations—recognizing that AI optimized for one context may not generalize to others. Leading research institutions now require AI-driven studies to report demographic composition of training data, test performance across subgroups, and discuss limitations—standards aiming to prevent biased AI from creating or exacerbating scientific knowledge gaps.

Balancing prediction and understanding represents a fundamental tension: AI systems that achieve high predictive accuracy without causal explanations provide limited scientific value compared to theories that illuminate mechanisms even with imperfect predictions. Physics has traditionally prioritized understanding (elegant equations explaining phenomena from first principles) over pure prediction—but AI inverts this priority, optimizing for predictive performance without necessarily providing mechanistic insight. Some researchers argue this shift is acceptable: if AI predicts which drug candidates will succeed clinically, mechanistic understanding is less critical than practical results. Others counter that science without understanding is mere engineering—we cannot design new interventions, anticipate failure modes, or build trust in AI recommendations without comprehending underlying mechanisms. The optimal path likely involves hybrid approaches where AI identifies patterns, then humans develop theoretical explanations for those patterns—iterative collaboration between machine prediction and human interpretation, each informing the other.

The Future of AI in Scientific Discovery

Scientific AI continues advancing rapidly through larger models, better algorithms, expanded datasets, and increasingly sophisticated human-AI collaboration paradigms. Several trends will shape the next decade of AI-driven science.

Autonomous laboratories combine AI with robotic automation to conduct experiments without human intervention, creating closed-loop discovery systems. Carnegie Mellon’s Coscientist AI integrates large language models with laboratory robots, successfully planning and executing organic chemistry experiments including synthesizing aspirin, optimizing reaction conditions, and discovering novel synthetic routes—all autonomously with humans only verifying safety. The system reads scientific literature to learn experimental procedures, generates hypotheses about optimal reaction conditions, instructs robots to perform experiments, analyzes results, then iterates based on outcomes. While current systems require human oversight and handle only simple experiments, the trajectory points toward AI laboratories operating 24/7, systematically exploring experimental space faster than human researchers could—potentially accelerating empirical science by orders of magnitude.

Foundation models for science apply the large-scale pre-training paradigm successful in natural language processing to scientific domains. Meta’s ESM-2 protein language model, trained on 65 million protein sequences, learns representations capturing evolutionary relationships, structural constraints, and functional properties—enabling zero-shot prediction (making useful predictions for proteins never seen during training) and transfer learning (fine-tuning for specialized tasks with minimal additional data). Similarly, MatterGen from Microsoft trains on millions of crystal structures, learning representations of materials space that transfer across prediction tasks. These foundation models democratize AI science—researchers without machine learning expertise can fine-tune pre-trained models for their specific problems rather than training from scratch, analogous to how GPT-4 API enables natural language applications without requiring AI expertise. Open-source releases of scientific foundation models through platforms like Hugging Face accelerate adoption and enable researchers globally to leverage AI capabilities.

Multimodal scientific AI integrates diverse data types—experimental measurements, literature text, molecular structures, microscopy images, genetic sequences—into unified models that reason across modalities. Scientific understanding requires synthesizing information across disciplines: drug discovery benefits from integrating chemical structures, biological pathway data, patient clinical records, and literature describing disease mechanisms. BioGPT and similar systems combine language models with molecular encoders, enabling queries like “design a small molecule inhibiting BRAF kinase with better brain penetration than vemurafenib” that require understanding chemical structures, biological targets, and drug properties expressed in natural language. Multimodal integration mirrors how human scientists synthesize knowledge across sources—AI systems that replicate this synthetic capability will likely achieve breakthroughs inaccessible to single-modality approaches.

Ethical and safety considerations grow increasingly important as AI’s scientific capabilities expand. AI-designed molecules could include potent toxins, bioweapons, or addictive drugs—requiring responsible disclosure practices and access controls. Some researchers advocate publishing only high-level descriptions of dangerous capabilities (demonstrating that AI can design toxins, without publishing the actual toxic molecules), while others argue that secrecy impedes scientific progress and independent validation. The tension between scientific openness and security remains unresolved, with different research groups adopting varying policies. AI climate models that suggest geoengineering interventions (deliberate climate modification) raise questions about governance: who decides whether to implement AI-recommended climate interventions with planetary-scale consequences? Ensuring that AI serves humanity’s interests requires proactive governance frameworks developed in parallel with technical capabilities—an interdisciplinary challenge requiring scientists, ethicists, policymakers, and publics.

Conclusion and Strategic Implications

Artificial intelligence is fundamentally transforming scientific discovery across disciplines, accelerating timelines from years to months, reducing costs by orders of magnitude, and enabling insights inaccessible to human analysis alone. Key takeaways include:

- Drug discovery acceleration: Insilico Medicine’s AI-designed drug reached Phase II trials in 18 months and $2.6 million—75% faster and 95% cheaper than traditional development

- Protein structure revolution: AlphaFold 2 solved the 50-year protein folding problem, providing structures for 200+ million proteins accessed 10+ million times by researchers worldwide

- Materials expansion: DeepMind’s GNoME discovered 2.2 million novel stable materials—800% increase in known compounds, with 736 already experimentally validated

- Climate modeling improvement: Hybrid physics-ML models achieve 100-10,000× speedups enabling high-resolution ensemble projections previously computationally infeasible

- Reproducibility challenges: Only 23% of AI-driven research papers provide sufficient detail for independent reproduction, requiring improved transparency standards

The future of science involves human-AI collaboration where machines generate hypotheses and predictions while humans provide creativity, intuition, ethical judgment, and theoretical understanding. Organizations and institutions that embrace this partnership—investing in AI capabilities, training scientists in AI literacy, and developing responsible AI practices—will achieve competitive advantage in discovery while those resistant to AI augmentation risk falling behind. However, successful integration requires addressing challenges including reproducibility, bias, interpretability, and safety through thoughtful governance ensuring AI accelerates beneficial discovery while preventing misuse and maintaining scientific rigor.

Sources

- Zhavoronkov, A., et al. (2024). Discovery of novel therapeutic targets using AI-powered biological inference. Nature Biotechnology, 42, 47-53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02068-0

- Jumper, J., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596, 583-589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

- Merchant, A., et al. (2023). Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature, 624, 80-85. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06735-9

- Lam, R., et al. (2023). Learning skillful medium-range global weather forecasting. Science, 382(6677), 1416-1421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi2336

- Boiko, D. A., et al. (2023). Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature, 624, 570-578. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06792-0

- Senior, A. W., et al. (2020). Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature, 577, 706-710. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1923-7

- Sanchez-Lengeling, B., & Aspuru-Guzik, A. (2018). Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science, 361(6400), 360-365. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat2663

- Wang, H., et al. (2021). Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature, 620, 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06221-2

- Stokes, J. M., et al. (2020). A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell, 180(4), 688-702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.021